Are We Living Too Long? An Abingdon Chiropractic Perspective

Life Expectancy: The Double-Edged Sword

In recent decades, human life expectancy has seen a significant increase. For example, life expectancy at birth in the European Union rose from about 69 years in 1960 to approximately 80 years in 2010. If this trend continues, a child born today could expect to live around 100 years.

However, this increase in lifespan often does not correlate with a higher quality of life in the elderly. The increase in life expectancy has been accompanied by a rise in age-related diseases, disabilities, and dementia, raising crucial questions about the focus of medical research. Should we aim to further extend life expectancy, or should we prioritise reducing the effects of ageing and chronic diseases?

Figure 1 - The percentage of people in England & Wales 2011 reporting ‘Good health’, or ‘Disability’ in different age ranges.

The Dilemma: Good Health vs. Disability

While we are living longer, the additional years often come with significant health challenges. As people age, they are more likely to develop conditions like cancer, heart disease, dementia, and arthritis.

For instance, the prevalence of dementia increases dramatically with age—from 0.6% in those aged 60–64 to 41% in those aged 90–94 in Europe. Consequently, disability becomes more common, with over 80% of the UK population aged 85 and older reporting some form of disability.

This trend suggests that while we are adding years to our lives, the quality of those additional years may be declining.

Figure 2 - A longitudinal study indicating decline of cognitive abilities after 70 years.

The decline of cognitive abilities after 70 years old

Even in the absence of disease and disability, human abilities including memory, cognition, mobility, sight, hearing, taste and communication decline with age (Fig2), so that the quality of life for someone older than 90 years is on average very poor. Given the increasing prevalence of multiple diseases, disabilities, and dementias at high age, it is not obvious that just extending lifespan beyond 90 years of age is a worthwhile undertaking. Consequently, it is unclear why we are currently investing so much money in cancer and cardiovascular research aimed at reducing death rates in the elderly, if the consequence is more years lived with disease, dementia, disability and advanced ageing.

Perceptual speed - The ability to quickly and accurately compare similarities and differences among sets of letters, numbers, objects, pictures, or patterns.

Verbal memory - Memory capability, learning of word lists, story recall (or logical memory), and learning of sequences of paired words.

Numerical ability - The ability of an individual to execute tasks relating to the handling of numbers.

Economic Implications: The Pension and Healthcare Crisis

The rising number of elderly individuals, many of whom live with chronic conditions, places a significant strain on healthcare systems and pension funds.

Public policy in the past century has focused on reducing mortality rather than addressing the root causes of ageing.

As a result, while the average lifespan has nearly doubled, the rate of ageing has not decreased, leading to a greater prevalence of age-related diseases.

This imbalance creates economic challenges, as extended lifespans without a corresponding reduction in ageing increase the costs associated with pensions and healthcare.

Medical research and funding

We need to consider the relative costs and efficacy of investing in medical research to reduce morbidity versus mortality. It could be that it is more difficult and thus more costly to reduce morbidity and ageing than to reduce mortality. The record of the past century indicates that wherever significant efforts and resources have been invested, there has been success to reducing morbidity, including pain relief, arthritis, infections, sight, hearing, mobility, schizophrenia and depression. This suggests that the greater progress in reducing mortality may simply be due to the greater funding and attention that has been paid to it. Age-related disease is one such feature of ageing, and there is no biological reason to believe that reducing ageing is any more difficult than reducing mortality. One might be tempted to argue that ageing is natural and therefore humans should not tamper with it.

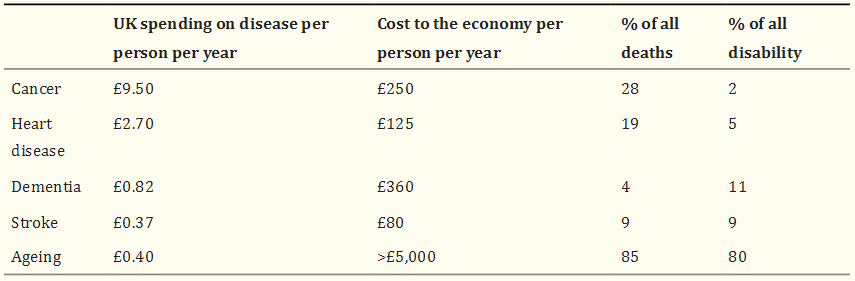

Current government and charity funding of medical research are influenced by a variety of factors, but the relative funding on different diseases appears to be more heavily influenced by the contribution to mortality than their contribution to morbidity (Fig3). For example, 10 times as much is spent on cancer as on dementia research in the UK, although dementia contributes 5 times as much morbidity as cancer. Generally, funding for ageing research is tiny compared to its huge impact on mortality, morbidity and the economy. So why do governments and charities provide more funds for medical research that focuses on increasing quantity rather than quality of life? One possible answer is that politicians believe, or believe that other people believe, that death trumps disease, that death is more terrifying than disease and ageing or that preventing death is more essential to health than increasing quality of life. However, such beliefs, if they exist are misguided because everybody dies eventually and we can not eliminate death.

Figure 3 - UK spending, cost to the economy, % of deaths and % of disability attributed to different diseases and ageing.

Figure 4 - A managed compression of morbidity.

Quantity vs Quality of Life

Should public policy favour increasing the quantity or quality of life? Life expectancy is currently increasing more rapidly than healthy life expectancy (average number of years lived in good health), so that morbidity (average number of years lived in poor health) is slowly expanding in The European Union. We need to actively compress morbidity (Fig4) by switching medical research funding from causes of death to causes of ageing and age-related morbidity. If successful, this would slow the rate at which life expectancy increased and speed the rate at which healthy life expectancy increased, resulting in a compression of morbidity, and making it worth extending lifespan further. Doing so is likely to be cost neutral in the short term and cost beneficial in the long term by reducing healthcare and pension costs. More importantly, it will reduce the chances of degenerative disease, disability, dementia and extreme ageing for ourselves and our children, hopefully enabling a better quality of life and end of life for us all.

But do people care more about the quantity than the quality of life? A recent survey of more than 9,000 people across seven European countries, which explored people's priorities when confronted with a serious disease and had less than one year to live, found that 71% thought it more important to improve the quality rather than the quantity of life for the time they had left, 4% thought it more important to extend life irrespective of quality, and 25% said both quality and extending life were equally important. A similar survey of Americans found that they believe it is more important to enhance the quality of life for seriously ill patients, even if it means a shorter life (71%) than to extend their lives through every medical intervention possible (23%). It appears that people generally favour quality over quantity of life. Therefore, governments and charities should not assume that people favour medical research that extends quantity rather than quality of life.

Key points and considerations…

Given the increasing rate of multiple disease, disabilities, dementias and dysfunctions at high age, it is not obvious that just extending lifespan beyond 90 years of age is a worthwhile undertaking.

Should medical research be focused on increasing the quantity or quality of life?

The result of life extension, without reducing ageing, has increased the extent of ageing and age-related disease, plus pension, social and NHS costs in an unsustainable way.

Surely now the time has come for medical research to refocus onto reducing ageing and age-related morbidity, thereby increasing both our health and our wealth.

What are your perspectives on this blog? Did you enjoy this article? Drop a comment below or email karl@focuschiropractic.co.uk

References

(1) Brown, G.C. (2015). Living too long. European Molecular Biology Organization Journal.